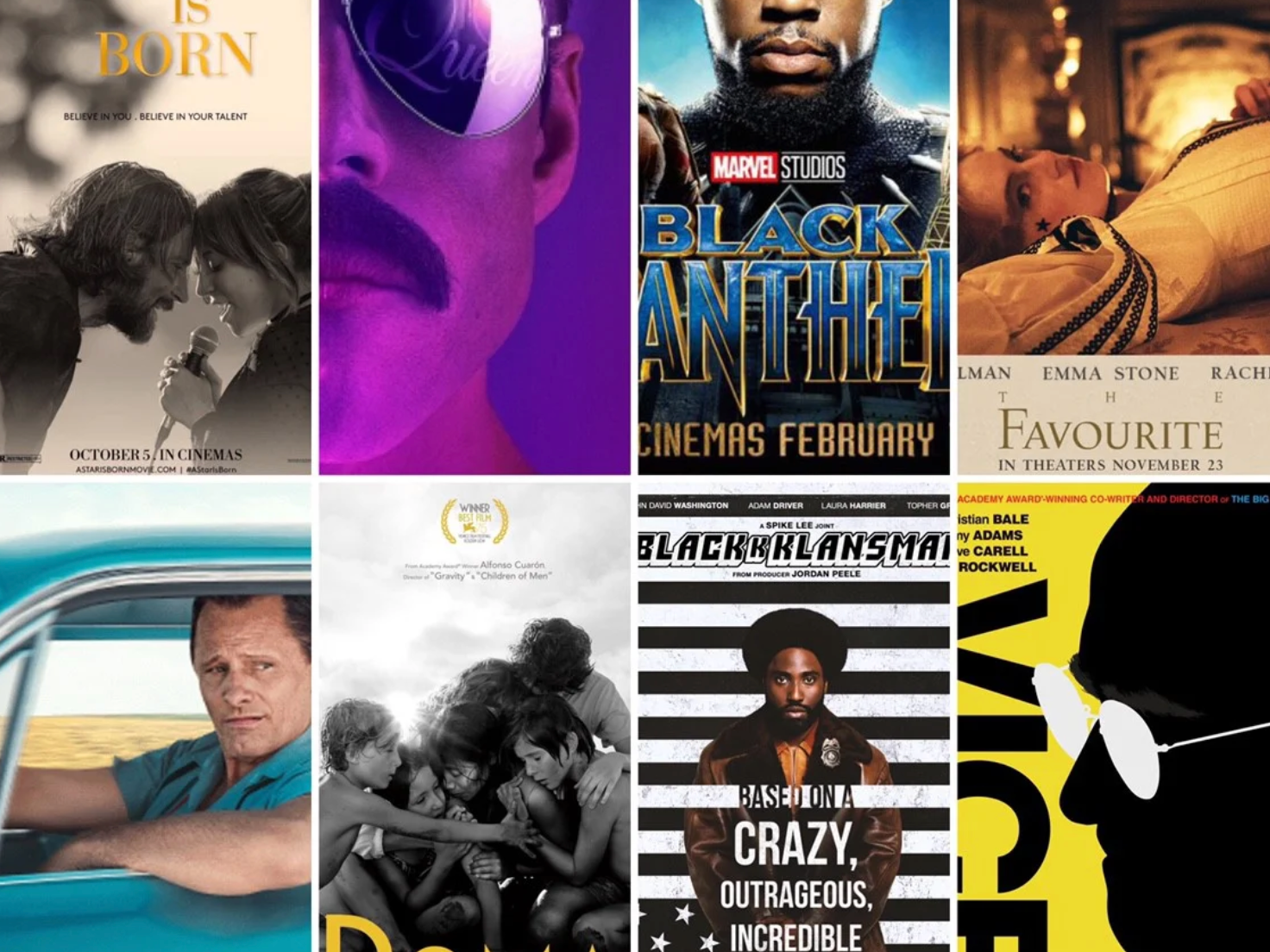

Every year around the time that award show nominees begin to be released or casting decisions are made, the same debate over the lack of representation in Hollywood is put forward. The industry continues to without fail under-represent women, people of color, the disabled, and LGBTQ people. Hollywood films disproportionately show upper-middle class, white, cisgender, heterosexual men’s stories, and the same disproportionate representation exists behind the production of these films as well. Directors, writers, producers, and the other figures that dominate the industry behind-the-scenes both contribute to this unequal representation by creating and platforming traditionally white stories as well as by serving as gatekeepers for the industry, limiting the minority voices from creating media to tell their personal unheard stories. University of Southern California’s Annenberg Inclusion Initiative (AII) released a report that looked over the representational statistics in Hollywood from 2007-2017. This report found that there has been no major significant shift in the characters of the films released that year. Director of the initiative, Stacy L. Smith, said that they did not find “an interesting trend either downward or upward across multiple years to suggest there’s a concerted effort to be inclusive.” The industry has not been inclusive or even tried to operate outside of its established formula. Many of the reports that break down the percentages of characters in films use their designations for the characters, and not the actors, meaning that a character coded as being of color of a sexual minority played by a straight or white character adds to the minorities ‘representation’. Media is being created that features crews and stories from under-represented people, but often these products are indie and out of the mainstream, something that is not recognized to the degree that a traditional white story from white creators is. This is why something like Moonlight or Crazy Rich Asians breaking the precedent and receiving both mainstream and critical acclaim is so noteworthy, and why a big box-office breaking company like Disney/Marvel making a place for superheroes to be women, black, and/or queer has been so long-awaited.

The report from the AII showed that when analyzing the top 100 films from each year between 2007 and 2017, only about 30% of all speaking characters were female-identifying, and those characters are also more likely to be sexualized in the film. 25% of women in film will appear nude while for men the number is only 9%. The breakdown for gender is drastic, but the numbers for race representation are even more alarming with almost 71% percent of characters in film being white. Priscilla Frank noted in her analysis for the Huffington Post that these numbers are a stark contrast to the actual breakdown of race in the United States. She noted that in 2016, only one film out of the 100 analyzed had a percentage of Latinx characters that accurately reflected the population breakdown within the United States. An even starker statistic to note is how many films do not provide that representation to women of color: 47 of the films looked at in 2016 did not feature any black female speaking character, 66% did not feature a speaking role for Asian women, and 72% did not feature any speaking roles for Latin women. LGBTQ characters also did not have proper representation in the top 100 films of the year, with less than 25% of the films giving a speaking role to an LGBTQ character, and of those characters about 80% were white. A research scientist on the report, Katherine Pieper, noted that “Diversity is not just something that happens, it’s something you have to think about and aim for as an objective and achieve.” It’s not something that just happens, but it especially does not happen when backstage Hollywood continues the same issues of unequal representation. In 2016 only 4.2% of directors were women and only 12.2% of screenwriters. And still, most of those positions are going to white women. Of the 900 films that were looked at in the report, only 5 were directed by women of color. Smith said that “We really see that there’s exclusion when it comes to who’s getting to call the shots, [minorities] are not getting the opportunity. And our findings present a pretty condemning portrait of exclusionary and discriminatory hiring practices.” This immense inequality in Hollywood is only reinforced through the AII report. People want diversity and a proper representation that matches the consumers who supply the industry with ticket sales and butts-in-seats, but it will take more work for an actual change to end up happening.

Smith linked this dominance behind the scenes to nepotism and behind-closed-doors deals between friends and closed networks. “Studies don’t move the needle. Everybody likes to get the attention of drawing the focus on the issues but that’s not what moves the needle. Changing hearts and minds, that isn’t what changes this problem.” What people need to do, Smith says, is express their resistance to the way that Hollywood has done business and make them change the way that they hire. “Access and opportunity should be given to individuals that are talented, qualified, and available for the job and that’s not how these deals are being brokered, so until hiring is targeted and activists rally around that one key exclusionary preface, these numbers won’t move.” We are not going to see any major changes in who we see on the screen until those hiring changes change in Hollywood.

The representation issue has been brought into the spotlight again recently because of a couple of very notable casting decisions: the casting of black actress Halle Bailey as Ariel in Disney’s new live-action remake of The Little Mermaid, and Scarlett Johansson’s comments about her casting and eventual step-down from the role of transgender man Dante “Tex” Gil in the year before. Some very vocal people on sites like Twitter and Facebook were upset when Bailey was cast as Ariel the Mermaid, a choice that goes defies Disney’s original interpretation of the character as a white mermaid with red hair. Fans of the original story were quick to point out that this would not be accurate to both the original Disney animated film as well as the original Dutch Hans Christian Anderson story that the film is adapted from. Those quick to condemnation fans will not be as quick to point out that a mermaid’s skin color can be anything, a mermaid is not real and can be drawn/understood in any way, a Dutch mermaid can exist under any skin color as any human Dutch person can. Additionally, original voice actress for Ariel, Jodi Benson, added her take in regards to her performances, “let’s face it, I’m really, really, old - and so when I’m singing ‘Part of Your World,’ if you were to judge me on the way that I look on the outside, it might change the way that you interpret the song. But if you close your eyes, you can still hear the spirit of Ariel.” She believes that the spirit of the character is what is important, not what the character is visually translated to be.

Scarlett Johansson’s controversy was a little different. Rather than be attacked online for being an underrepresented actor of color playing a role of an originally white character, Johansson has been criticized for being a white actor of privilege and having the position that “as an actor I should be allowed to play any person, or any tree, or any animal because that is my job and the requirements of my job.” She was going to play the transgender crime kingpin Tex in a film before being pressured out of the role, and her portrayal of Japanese character Motoko Kusanagi in the American live-action remake of the Ghost in the Shell anime film was also criticized for “whitewashing,” especially considering that her character in the film’s name changed to a westernized Mira Killian. The Hollywood industry has for a long time believed that the casting of non-white actors in leading roles would bring less profit, Marc Bernardin of the Los Angeles Times wrote that “the only race Hollywood cares about is the box office race.” Straight white actors have been playing different races and sexualities in film since the beginning of Hollywood, but since the underrepresented can be heard now more than ever, these performances have been reviled and almost condemned by the public. But for the most part, Hollywood has still been Hollywood: Rooney Mara played the Native American Tiger Lily in Pan (2015), Emma Stone played the mixed-race Captain Allison Ng in Aloha (2015), Ben Affleck played Hispanic-American Tony Mendez in Argo (2012), etc. It has been going on forever, but with how saturated the market is now with streaming platforms like Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon, these big Hollywood studios may finally be understanding that people of color, disabled people, women, and sexual minorities have places in Hollywood.

Not every story is about white people, and not every story with a white protagonist has their whiteness be pivotal to the story. The whiteness of characters such as Spiderman, James Bond, or Ariel the Mermaid, is not something that directly creates the character or their mythology; their whiteness was just a choice from the creators that reflected themselves as well as the culture and industry of the time that they were created in. Whiteness was seen as the baseline and another color or race seemed to be something extra. This is partially due to the social conditioning of constantly seeing straight white faces in the media. In the Hunger Games book series, the main character Katniss Everdeen is described somewhat ambiguously in regards to her race, but instead of leaving the ambiguity and trying to find the perfect actress the casting agents searched for someone who “should be caucasian.” White people may feel like they are being attacked for not being able to “act” and perform any role under the sun, but for so long the people of Hollywood who have defined storytelling have defined it as being for and by white people. Actors like Scarlett Johansson have the luxury of all the roles under the sun looking for white actors, but she also feels like she should be able to play the role of a transgender man or Asian woman, roles that those minorities are almost exclusively only able to obtain. Someone like Johansson taking that role takes it away from someone who may only be able to have that role and not be able to go play any of the other roles that Johansson can land. The inclusion of minorities does not limit the wide spectrum of creativity in storytelling, it allows for original stories to be told by those who have personal relationships with those roles and not have their people’s image defined by Hollywood, they can have it defined by them.